It no longer comes easily to me, the stillness within which I can spend hours with a book. (That nearly three years have passed since I wrote on here should be an indication, no?) The reasons for how suddenly flighty this particular brand of stillness has become are myriad, and would require me to delve into a (most likely digression-laden) review of the last three years. The précis: I have become, in these past three years (and in the last year more so), the woman who once long ago read a lot of books.

As a result of my inability to access that stillness, I have found myself turning on books, by demanding more from them than I already had. (And here, the parenthetical: Back when I read.) Specific demands that need to be met to ensure I am tethered to the pages to their completion—as I’ve been, dear whoever-is-still-out-there, rather aimless and restless. And so: I need my books immersive and just as greedy for my time—I needed books that talk to me, and provoke me into talking back. I need to be provoked into making notes, into scribbling on the margins; I need to be provoked into stepping within the world the book has made, and I need that world to engage me and magick me into staying. I need books that silence the frenetic white noise that’s been in my head these past years.

All of that, on top of a core readerly tenet: I need to find myself in the books that I read. I’ve written about this before, nearly four years ago: The cost of reading so personally, so inwardly. And, subsequently, the cost of being grounded on radical honesty while writing about books—pointing to a phrase, for example, to say that it defines me; marking the pages where a character is frantically looking for her self-destruct button, and telling all of you that I have come to realize my inevitable bouts of tendresse for self-sabotage. (“I work once again,” I also wrote before, “toward a more straightforward untangling of feeling: I just need to find the perfect alchemy of nerve and ambivalence; hone perhaps-dormant skills re: knowing what to divulge and what to imply, and in what manner: Which book, or artwork, or film must bear the mantle of ushering intimacies?”) (I remember now how an ex-boyfriend found it amusingly odd, a curiouser idiosyncrasy, that I would insist on there being a me somewhere in the book; that I have to recognize what I know of myself within sentences; that I wanted sentences to articulate things about me, my thoughts, my feelings, my desires, my longings, my frustrations, my rages. And I remember now, too, thinking how peculiar it was that he didn’t do the same thing. What else were books for, foremost, but for the unvoiced selves?)

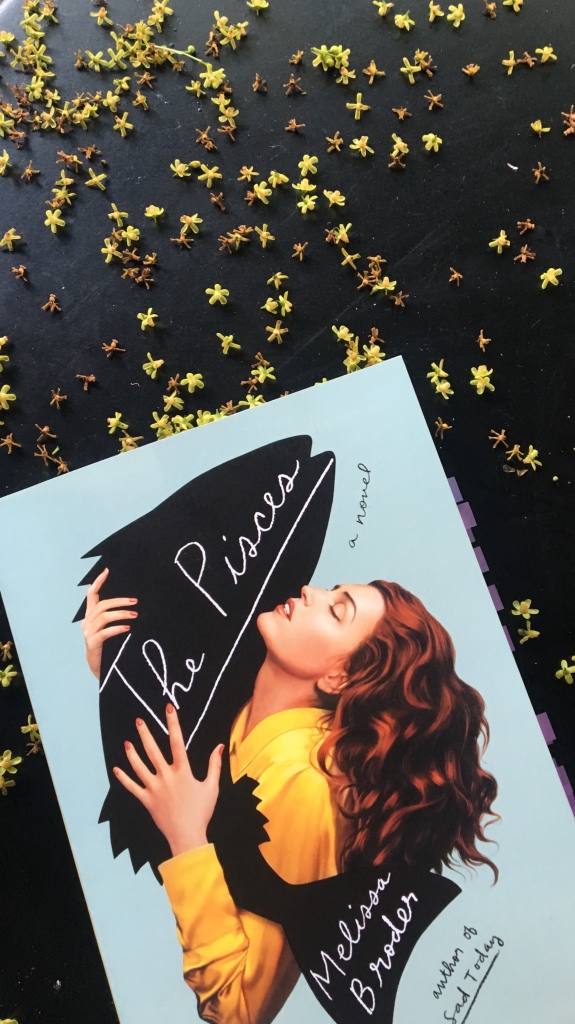

And so it is, perhaps, quite fitting—and maybe even rather telling—that the first novel I’ve read comfortably—that is, without teeth-gritting restlessness, and with that frenetic white noise in my brain quieted for as long as I was in these pages—is The Pisces by Melissa Broder. This, by the way, was not my first brush against Broder’s work—I had eagerly acquired her earlier book of essays, So Sad Today, and I had selfishly longed for it to define a particular kind of sadness: That is, mine. Instead, I found strange-to-me compulsions and quirks; sadness as a millennial badge of honor, loneliness as jacket one can pull on and off at a whim. It was not about sadness, of today or other days; it was not about my sadness, or anyone else’s. It was just hers, and this failure to create a more universal world for all the sad and lonely people to dwell within made that book to me vapid, void of anything meaningful or even eloquent and lyrical; it was sadness for sadness’ sake.

I always thought of depression as having no shape. When it manifested as a feeling of emptiness, you could inject something into it: a 3 Musketeers, a walk, something to kind of give it a new form. You could penetrate it and give it more of a shape you felt better about. But this was something new, like a thicker, gooey sludge. It had its own shape. It could not be contained. It was a terror. Of what I was terrified I couldn’t exactly say, but it was sitting on me. Every other shape was being absorbed into it.

And yet I picked up The Pisces at a bookstore, my inner sneer beginning to form, though I remained convinced that this was a book I couldn’t read fundamentally because I could not read at all, not in my condition. But I opened The Pisces—it begins with our heroine Lucy talking about loneliness, and the needful appreciation of an animal, and the consideration that perhaps this was what a lonely person should settle for: The pure love of a creature who takes you at face value, a creature who didn’t need much from you for you to inspire its devotion. I read that first paragraph, and I read the second paragraph, and then I’d read the first page, and then I’d read the first section—still, quiet, lost in the book, pressed close against the shelves so as not to bother anyone else, running late for an art opening exhibit. I was engrossed in that glorious pile of sentences—there had been, for me, a lightning bolt of recognition. Here was one Lucy greeting me with, “I was no longer lonely but I was,” and I had to respond. It had been a long time since I took home a book with me this way—a long time since I was compelled. It had been a while since a book was so clearly for and to me a mirror.

The Pisces was beautiful, radically so. Here was a book that turned melancholia into the mythic.

Would the pain begin to outweigh the beauty? How much pain would I have to get into before I gave up on pursuing beauty?

It was unashamed to delve into the lowest depressions of a person’s narrative—unashamed to be so crass about it; unashamed to air out the disgusting and repulsive poisons that are so much a part of who you are, you are basically them; unashamed to be so fucking revolting, as one can be when within the heart of desperate, romantic obsessions—as one can be when one is, simply, lonely, and feel very direly the need to be touched, to be seen, to be acknowledged, to be un-alone.

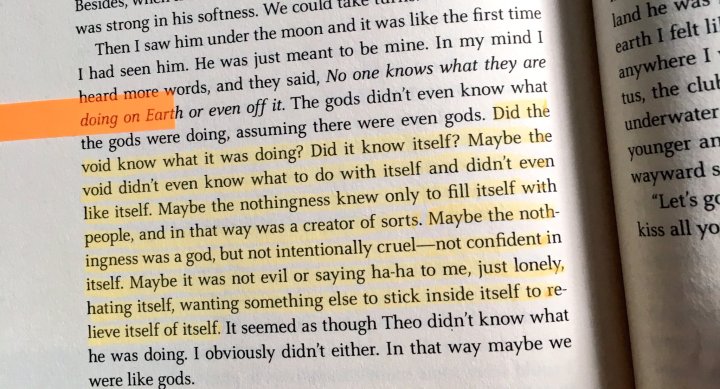

Maybe I didn’t need someone else to define me, but oh, I still wanted it. How vacuous was I? How empty was I that I needed a border drawn by someone else to tell me who I was? […] It was like a box in which to live: a boundary against the greater nothingness, to think one knew something about what others thought of you. It was there I could begin and end. And perhaps it was a prison, to have to begin and end, but it was also a relief.

Unashamed to delve, and hold up our poisons against the light.

… but the truth was there would never be enough to fill her need for attention—for devotion. That hole was bottomless. It was never-ending. […] No one really wanted satiety. It was the prospect of satiety—the excitement around the notion that we could ever be satisfied—that kept us going. But if you were ever actually satisfied it wouldn’t be satisfaction. You would just get hungry for something else. The only way to maybe have satisfaction would be to accept the nothingness and not try to put anyone else in it.

It was unashamed to be unpleasant, to carry truths.

She had given up on the thing that made her most alive, even if it made her the most crazy. […] You had to feel something truly heavenly to get over the chase. The chase was everything, all the hope and possibility of life. Very little else would be enough. Love itself would probably never be enough. You had to have the moment of almost touching, almost fucking, the moment right before he enters you for the first time, all the time.

And it had no qualms at being funny, to laugh at the ridiculous ways our sorrows manifest themselves—and never cruel, always empathetic, and never making you feel like it’s wrong to laugh at what is essentially yourself. It is—for all its lack of squeamishness, for all its edged fun-making, for all its profaneness—a very kind book.

I still didn’t love myself. I wasn’t sure how or when that was going to happen. But maybe it would if I continued to stay alive.

* * *

This week’s horoscope just came in, c/o Madame Clairevoyant—whom I’ve followed from The Rumpus to The Cut; astrology as a stopgap for the space Cheryl Strayed left when she stopped being Sugar—reads: “This is a week for textures other than softness, and for sounds other than quiet song. This week, something in your life might crack open, offering you something else, something harder, something that sparkles and reflects the sun’s light. There are different ways that a life can be good, and different ways to feel right in the world. Maybe this week is about a different relationship to the light, or maybe it’s about a changing relationship to desire.”

Earlier in Broder’s novel, her heroine makes one of the many resolutions that she would eventually break, by nature or circumstance: “You had to never get attached to any other person or expect anything to come to you, and that was how you fell in love with life and how maybe certain fun and good things could happen to you. They only happened as long as you didn’t need anything from anyone. As long as you didn’t take anything from anyone or give any part of yourself away to another person, but you just sort of met the other person in space, good things could happen. You had to fall in love with quiet first.“

I missed your words :) Great comeback btw! I’ve been meaning to pick this book up for a while now.

Is that a Hobonichi Techo I just spot there? :D