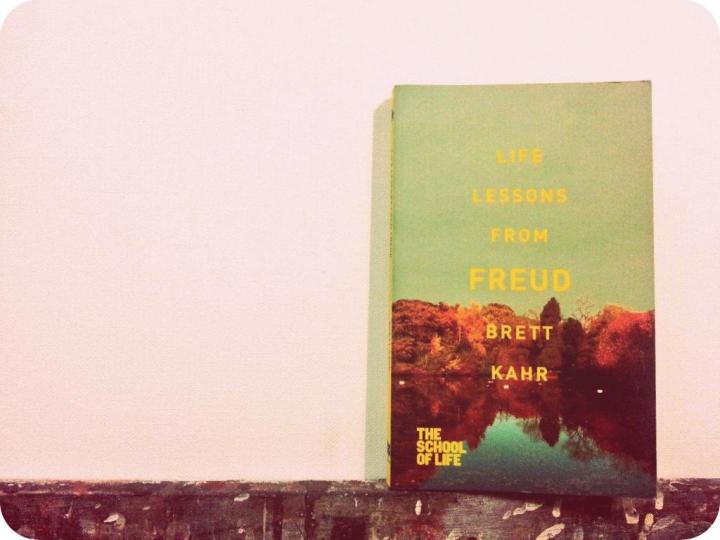

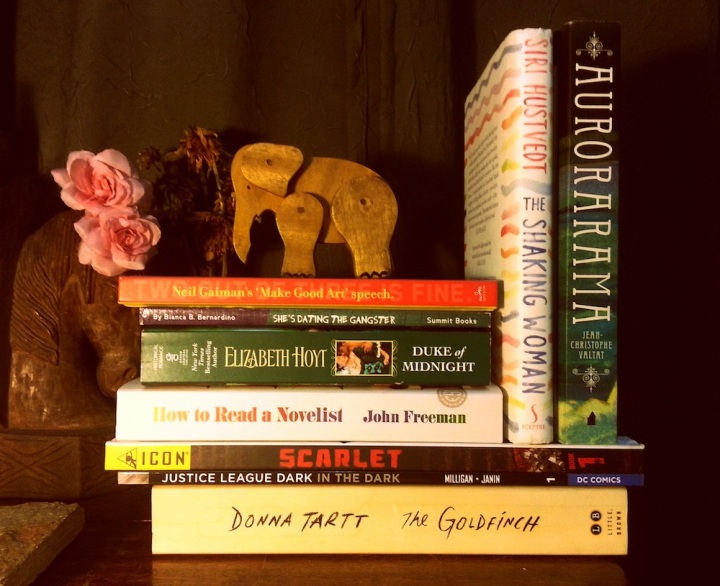

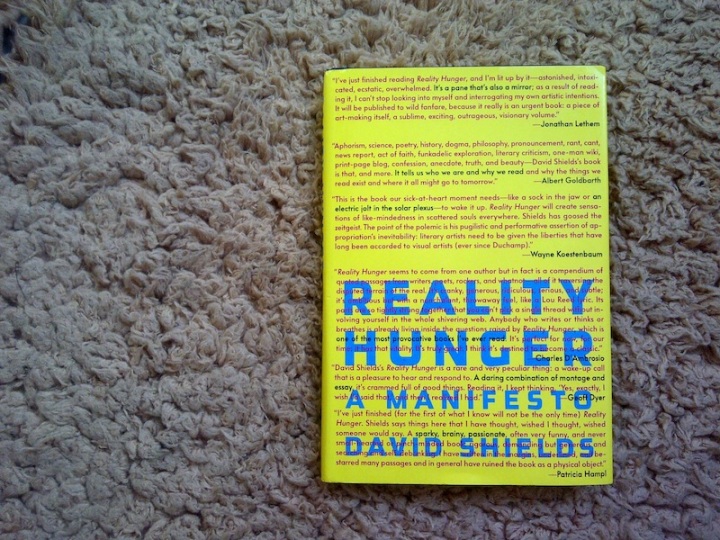

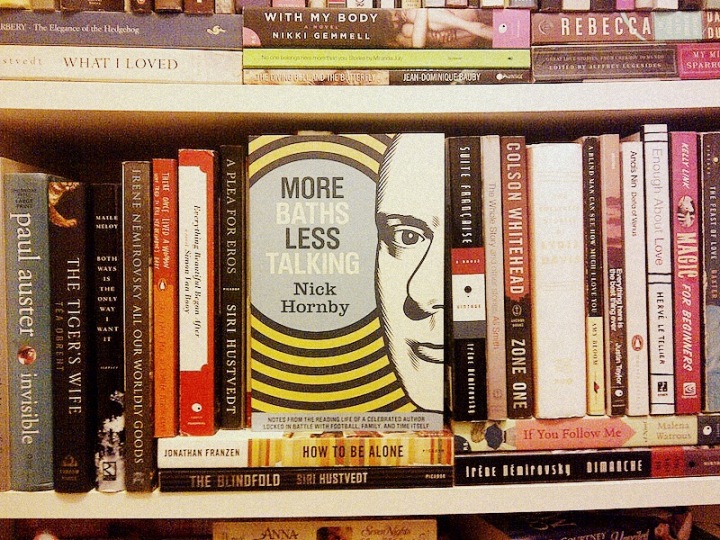

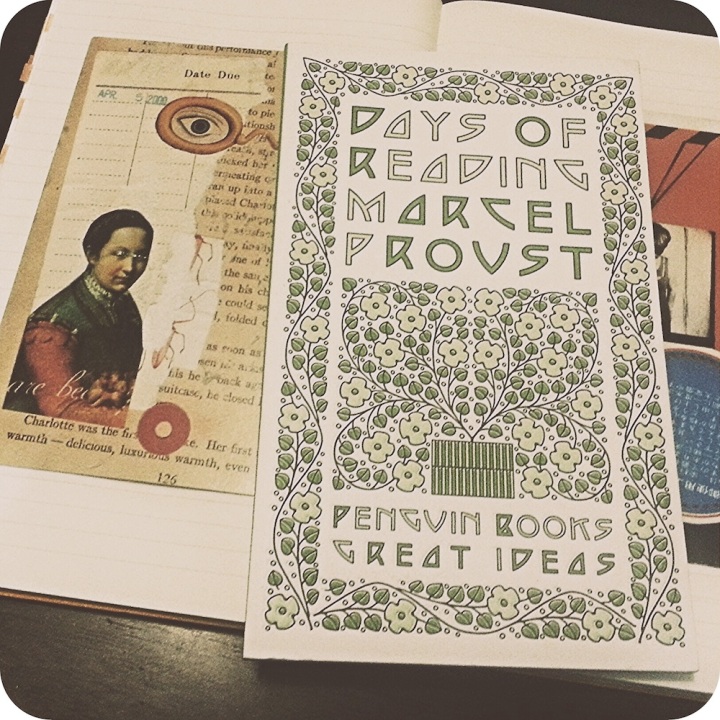

“For myself,” Marcel Proust writes, “I only feel myself live and think in a room where everything is the creation and the language of lives profoundly different from my own, of a taste the opposite of mine, where I can rediscover nothing of my conscious thought, where my imagination is exhilarated by feeling itself plunged into the heart of the non-self.” I feel immensely giddy that I am allowed a more literal interpretation: I am in the mad throes of love with my room. The good books are better, and the blows are softened when I’m with the books that don’t like me so much. I’m savoring every moment I have in this room, and I’m looking forward to the days and nights-into-days of reading that it will host. Sure: The detritus will find a way to rise, inch across my desk and on the floor; the books will ever so surely contrive a disarray; Real Life will intrude and I’ll be too weary to even try to stop it. But—and, yes, almost a chant of mine now—I will keep reading, I will immerse myself in what Proust rather earnestly dubs as “merely the noblest of distractions”—for as long as the floors gleam, for as long as I have a clear view of every book in the room, for as long as that red chair will hold me. And even after, of course—of course. [Continue reading.]